In her book The New Pakistani Middle-Class, social anthropologist, Ammara Maqsood observes that “most Pakistanis are painfully aware of how they are viewed by the world outside; they are perceived as a country of terrorists or, at best, backward religious zealots.”

During her fieldwork, Maqsood attended various cultural activities where she found predictability to these gatherings and would “often meet the same groups of people.” She writes that these events began to appear to her “like a rehearsal of some kind: the same faces, in the same roles, repeating the same dialogues. There was a staged quality to the events, where the conversation was directed not to each other but toward an uninitiated audience – an outsider.”

While Maqsood argues that it is this consciousness of an imagined outsider that gives these cultural events a “staged feel,” I would like to underscore the metaphors of “stage” and “rehearsal” that she uses to theorize cultural events in Pakistan as these are crucial to the way I am looking at the Karachi Literature Festival.

Bur first, it’s important to analyze KLF for what it’s able to achieve, before getting into why Maqsood’s analogy is an important lens to look at literature festivals in Pakistan.

KLF in numbers

In 2009, Ameena Saiyid, a former managing director of the Oxford University Press, Pakistan, attended the Jaipur Literature Festival in India. Inspired by the literature festival in Jaipur, she approached the British Council to sponsor a similar festival in Karachi, and upon agreeing, in March 2010, Saiyid along with Asif Farrukhi organized the Karachi Literature Festival (KLF) in Carlton Hotel in the Defense Housing Authority (DHA), one of the poshest districts in Karachi.

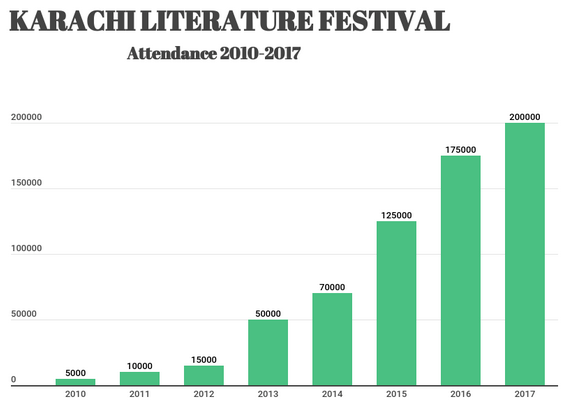

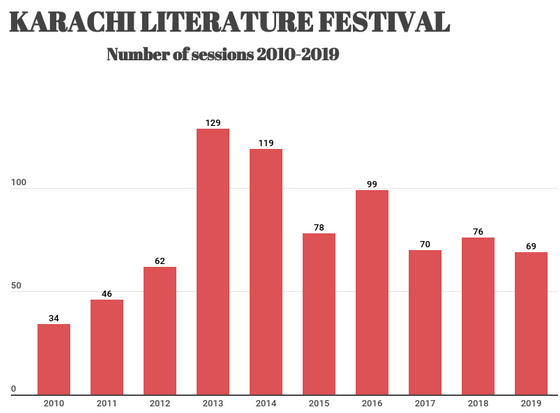

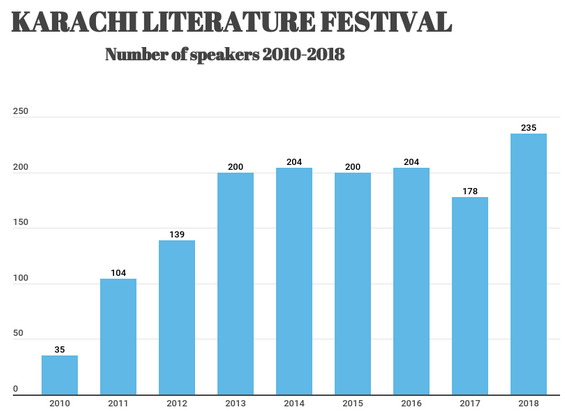

The festival lasted two days, had 34 sessions in two parallel streams and featured 35 writers. According to the KLF estimates, it was attended by “roughly” 5,000 people.

In 2011 the number of sessions increased to 46 in five parallel streams featuring 104 writers, speakers and performers, and the attendance grew to around 10,000.

In 2012, the festival grew even bigger and had 62 sessions in seven parallel streams with 139 writers, speakers, and performers, and was attended by nearly 15,000 people. In 2013, the festival became a three-day affair and moved to the Beach Luxury Hotel, accessible by public transport. The attendance rose to nearly 50,000 in 2013.

Since 2013, the festival is organized annually in the month of February.

The yearly increase in attendance from 2010 to 2017 is illustrated below:

Here, we see the number of sessions in each iteration of the KLF from 2010 to 2019:

The following graph shows the number of writers, speakers, and performers who have participated in the KLF from 2010 to 2018.

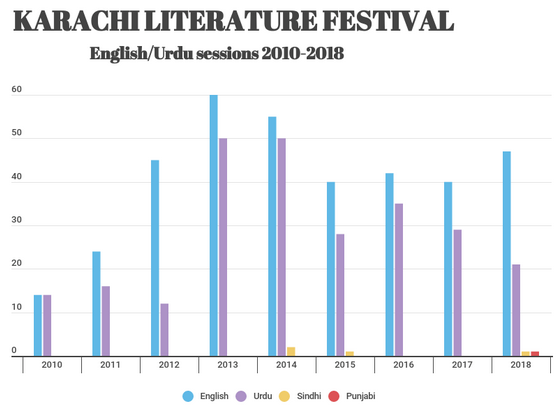

Ever since its inception in 2010, one of the most prominent features of the KLF has been its bilingual outlook. The sessions are conducted in English as well as in Urdu, the ‘national language’ of Pakistan.

Here’s a comparison of sessions conducted in English and Urdu.

Over the years the speakers invited at the Karachi Literature Festival have included writers, poets, academics, publishers, diplomats, journalists, bureaucrats, lawyers, economists, human rights activists, development sector professionals, architects, film and television actors, singers, dancers, and comedians, among others.

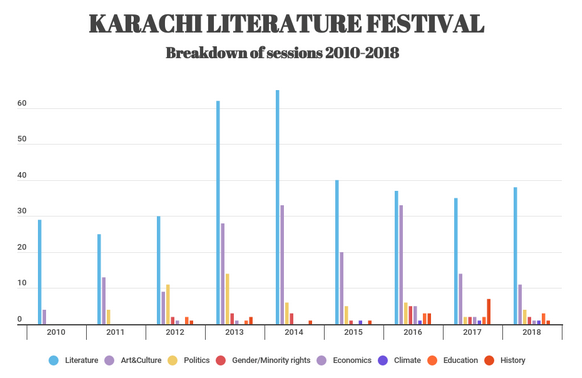

Every iteration of the KLF includes a variety of sessions that mainly focus on literature but also include sessions on art and culture, politics, gender and minority rights, economics, climate change, education, and history.

Below is a breakdown of sessions in this regard.

From 2010 to 2018, the sessions were planned and organized by a planning committee, which included Ameena Saiyid and Asif Farrukhi and the marketing staff of the Oxford University Press, Pakistan.

Ameena Saiyid retired in December 2018 after serving for thirty years with the Oxford University Press, Pakistan, and has since started along with Asif Farrukhi another literature festival called the Adab Festival.

Behind the scenes: Who pays for it?

The Karachi Literature Festival is free to attend, and one does not need any ticket whatsoever to attend the festival.

When I asked about why the festival is not ticketed, Asif Farrukhi, who organized the festival along with Ameena Saiyid from 2010 – 2018, says, “since they were able to cover all the costs through various sponsorships they kept it free because even a low-priced ticket will prevent students, especially from low-income families from attending the festival.”

Over the years, the festival has been sponsored by foreign cultural organizations like Alliance Française, Goethe Institute, American Institute of Pakistan Studies, Manchester Literature Festival, British Council, the Indian Council for Cultural Relations, as well as foreign embassies, including those of France, Germany, Italy, Brazil, the British Deputy High Commission, and the US Consulate General.

Universities like Habib University and the Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) have also sponsored the festival on a few occasions. In addition, the festival is sponsored by commercial enterprises like banks, pharmaceutical companies, beverage corporations, and airlines.

The festival does not pay the writers, speakers, or performers although all of their travel, accommodation, and food costs are paid for by the festival.

According to Farrukhi, the festival does not accept any funding from the government of Pakistan and does not invite any political figure who is holding a public office. He also told me that he and Ameena Saiyid, the founders and organizers of the festival, do not make any money from the festival.

But what’s the point of literature festivals?

In a telephonic conversation in January, I asked Farrukhi about his intentions and motivations for starting the Karachi Literature Festival back in 2010.

He told me that initially the festival was meant to promote a reading culture in Karachi and create a space for people who liked to talk about books and literature.

He also mentioned that Karachi, as a city, is often stereotyped in the Western media as a dangerous city swarming with terrorists; and although this view was “partially true,” there was much more to a city like Karachi and this stereotype of Karachi needed to be challenged.

According to the website of the Karachi Literature Festival, one of the objectives of the festival is “to provide opportunities through which the world can see and connect with the literature, culture, and social ethos of Pakistan.”

In a 2010 interview, Ameena Saiyid said that one of her objectives of starting the Karachi Literature Festival was to launch “a soft image offensive from Pakistan.”

My argument is that the Karachi Literature Festival is rather a “staged” event that is directed toward an imagined outsider who has to be convinced that Pakistan is not a “country of terrorists or, at best, backward religious zealots.”

Audiences who attend the Karachi Literature Festival could be understood as uncredited extras or background actors in a staged performance. And this repetition is not limited to the people the Karachi Literature Festival invited.

In order to explore the “staged” nature of the Karachi Literature Festival, I looked at the festival schedules and directory of writers, speakers, and performers who participated in the festival from 2010 to 2018.

Like Maqsood, I noticed the same names appearing again and again in these directories and schedules.

Expanding on Maqsood’s metaphor of a “staged” event, I am going to use the terminology that is employed with regard to a television series. Characters appearing in a television series are divided into different categories: regular characters appear in most or every episode or a television show; recurring characters appear frequently although not as frequently as regular characters; guest characters appear in a few episodes while bit players usually appear in one episode and their interaction with a principal actor is less than five or six lines of dialogue.

Sometimes, the sessions are also repeated, for example, a session by Fahmida Riaz in the 2014 KLF titled, Book Launches: Our Shaikh Sa’ di: A Selection from Gulistan and Bustan and The Simurgh and the Birds was repeated in the 2015 KLF under the title, “Readings from Our Shaikh Sa’di: A Selection from Gulistan and Bustan and The Simurgh and the Birds.”

Similarly, the content of speeches and talks by certain writers is also quite repetitive. A member of the regular cast of the KLF, Arfa Syeda Zehra’s various speeches made over the course of nine years illustrate repetition of the same content over and over, at times even verbatim.

On the other hand, audiences who attend the Karachi Literature Festival could be understood as uncredited extras or background actors in a staged performance. And this repetition is not limited to the people the Karachi Literature Festival invited.

Promoting a ‘soft image’ in English

Another feature of the Karachi Literature Festival that contributes to its “staged feel” is its use of English, a language that is restricted to a small social and cultural elite in Pakistan despite the fact that English is the “official language” of Pakistan and the business of the state is conducted in it.

As I showed earlier, the number of sessions in English is always more than the number of sessions in Urdu, the so-called “national language” of Pakistan. The only exception in this regard is the 2010 festival when the number of sessions in English is equal to the number of sessions in Urdu.

But even when the sessions are conducted in Urdu, they are framed in English, which is to say that the announcement of a particular session is usually done in English and the schedule of the festival is always printed in English.

Can Pakistani literature festival that is directed toward an imagined outsider lead to an organic discourse that is less self-conscious?

But the division between English and Urdu sessions is not as neat as one would expect because most Pakistani writers and speakers are bilingual and so they sometimes add a few lines of Urdu in a conversation that is otherwise mostly in English. Sometimes, members of the audience ask questions in Urdu in a session that was conducted in English.

Although Urdu is considered the “national language” of Pakistan and most Pakistanis can communicate in Urdu, it is still the mother tongue of a small minority in Pakistan. The mother tongues of the majority of Pakistanis are what are generally referred to as “regional languages” and include Punjabi, Pashto, Sindhi, and Balochi. Sessions in these regional languages rarely feature in the Karachi Literature Festival.

In the 2014 Karachi Literature Festival, I attended a session titled, “Baloch Literature and Landscape” featuring Ayub Baloch, a Baloch scholar, and Tariq Luni, a Baloch artist. The session was framed in English but conducted primarily in Urdu.

Ten minutes into the session, a prominent writer and politician who happened to be in the audience requested Ayub Baloch, who had started speaking in Urdu to switch to English because there was a foreigner in the audience. Ayub Baloch appeared visibly perturbed at the request to switch to English and the moderator of the session intervened to say that she would interpret Ayub Baloch’s talk in English later.

Ayub Baloch went on to speak in Urdu but the request to speak in English made by that politician speaks of an attempt to present “a soft image” of Pakistan to an outside audience.

An imagined audience?

An epiphenomenon is the Karachi Literature Festival has been its replication in other Pakistani cities like Lahore and Islamabad.

In 2013, Razi Ahmed, a native of Lahore and a graduate of the University of Chicago, launched the Lahore Literary Festival, and in the same year, the Oxford University Press, Pakistan expanded the Karachi Literature Festival to Islamabad, the capital of the country.

In 2016, Yaqoob Khan Bangash, a historian of Modern South Asia and a professor at the Information Technology University, Lahore, launched Afkar-e-Taza ThinkFest, which is “an academic literary festival” that aims to “bridge the gap between academia and society by becoming an interface between them.” All these literature festivals are modeled after the Karachi Literature Festival, which is to say that they are primarily conducted in English and are directed toward an imagined audience outside Pakistan.

It is also important to note that a number of writers and speakers who appear in the Karachi Literature Festival also appear in literature festivals in Lahore and Islamabad, which supports Maqsood’s observation regarding “the same faces, in the same roles, repeating the same dialogues.” These repetitive staged performances could also be understood as the reproduction of the point of view of a social and cultural elite.

But can Pakistani literature festival that is directed toward an imagined outsider lead to an organic discourse that is less self-conscious?

That remains to be seen.

Mushtaq Bilal is a Fulbright doctoral fellow at the Department of Comparative Literature at the State University of New York (SUNY) at Binghamton. He is the author of the book Writing Pakistan: Conversations on Identity, Nationhood, and Fiction.